Five Afghan women who refuse to be silenced

It was just a snowman. But as winter descended on a starving Afghan population, the heavy snow brought joy to a small corner of Kabul.

A group of young women had stopped next to the snowman to take selfies. As they giggled and looked at their phones, they could have been anywhere.

Then three Taliban fighters spotted them. They came closer - the women fled. With a smile, one stepped towards the snowman - which perhaps he thought was un-Islamic. He tore off the stick arms, carefully removed the stone eyes, the nose too. Finally, a swift beheading.

I had just arrived back in Kabul after 10 years away and had already been lectured by a member of the Taliban about my lack of understanding of Afghan culture. He claimed to know what was best for Afghan women. "Blue-eyed devils" (Westerners) had corrupted the country, he appeared to suggest.

Rather than take his word for it, I wanted to hear from women themselves. Many are in hiding, all fear for their future and some for their lives. There are still women on the streets of Kabul, some still in Western clothes and headscarves, but their freedom is under attack - the freedom to work, study, move freely and to lead independent lives.

I met women who had been forced into the shadows of a new Afghanistan, who took great risks to express their views freely. They could only do so anonymously - except for Fatima, who insisted on showing her face.

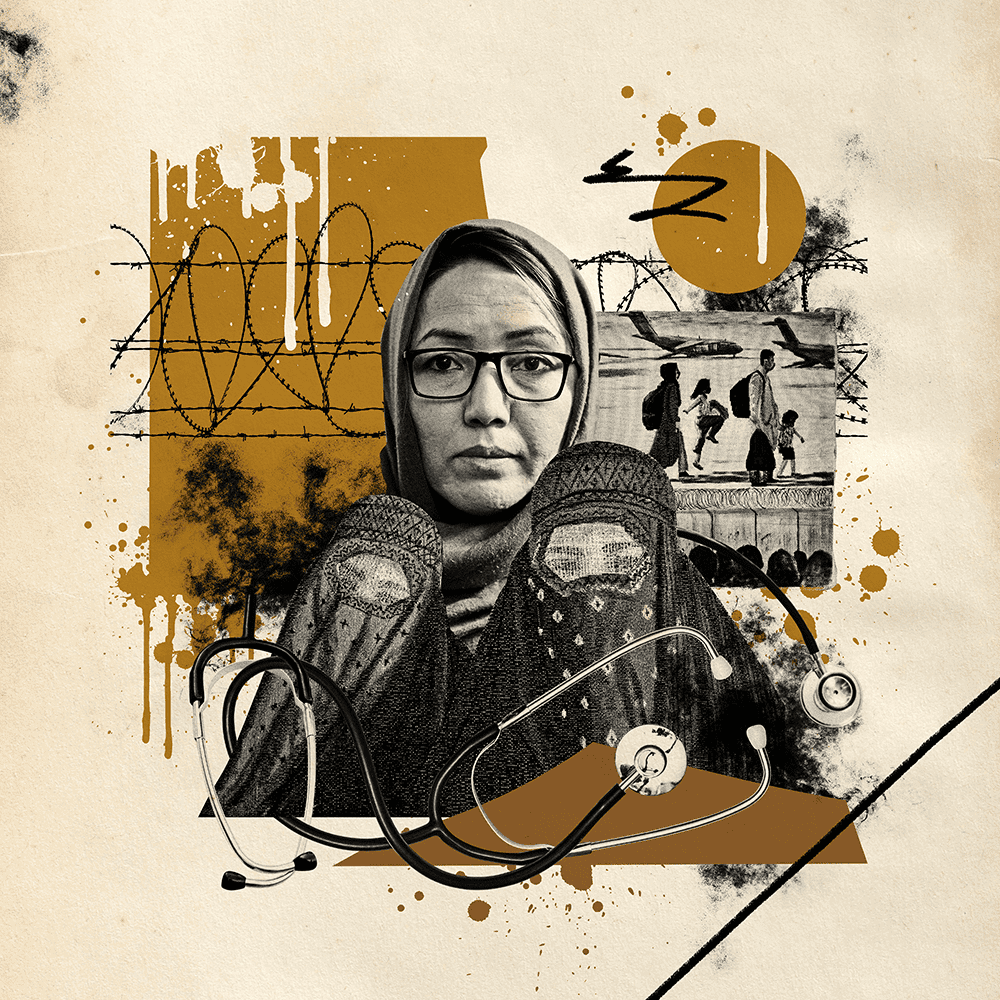

Fatima

Midwife, 44

The Taliban have stolen Fatima’s future twice. The last time they ruled Afghanistan, she was forced into marriage at the age of 14 and her education came to an abrupt end.

This time around, the 44-year-old midwife may still have a job, but like many women I spoke to, every-day life has diminished.

Fatima’s education and employment were hard won. After getting married, she didn’t resume her studies until she was 32. By then, the Taliban had long gone from power. But it still wasn’t easy - even under the new democratic Afghan republic.

I humbly request the Taliban do not meddle in women’s rights to education and employment. Otherwise, they are amputating one arm from the body of society

She says she did a number of fast-track courses within a short space of time - but there were times when she wasn’t allowed to study. “They would take one look at my ID card and say, ‘You are too old to sit in classes with other students.’”

She finally completed her degree two years ago - but again she faced another hurdle.

“It was hard enough for a girl to get educated in Afghanistan, imagine how difficult it was for an old married wife to get hired.” But Fatima succeeded and has since delivered thousands of babies.

“I wanted to work in an area where I would be able to train women,” she says. “When a woman is educated, she raises healthy and fruitful children. By doing so, she can present a meaningful child to society - one that will bring about change.”

Fatima appears to accept that Taliban control is likely to be permanent, but hopes this time around, they can govern differently.

“I humbly request the Taliban do not meddle in women’s right to education and employment,” she tells me. “Otherwise, they are amputating one arm from the body of society. Our society is made of two pillars, a pillar of men and another pillar of women. How can you run your life one-sided and one-handed?”

Fatima is fortunate in that she still has a job. “The Taliban cannot ban me from working in the hospital because they know that it is needed,” she says.

But she hasn’t been paid in months - and for that she blames Western sanctions, not the Taliban. “America and the international community have blocked Afghanistan’s money,” she says.

Fatima often works a 24-hour shift, delivering as many as 23 babies in that time. But there's no money to feed the patients or staff.

And she has a message for the US and the international community: “Sanctions on the Taliban will kill us faster than the violation of our rights by the Taliban. A girl dies from hunger and a mother either sells her daughter because of hunger or from pressure to marry her by force. The issue of their education and literacy is meaningless when you’re dying from hunger.”

Life, of course, isn’t just about work - and Fatima grieves for everything she has lost. She says she lies awake long into the night worrying. Her hair has started to fall out from the stress of the past five months. And there have been other changes too.

In her spare time, she is a tapestry artist. She shows me her work - representations of traditional scenes, such as the country’s national sport Buzkashi, where men on horseback fight to score goals with an animal carcass.

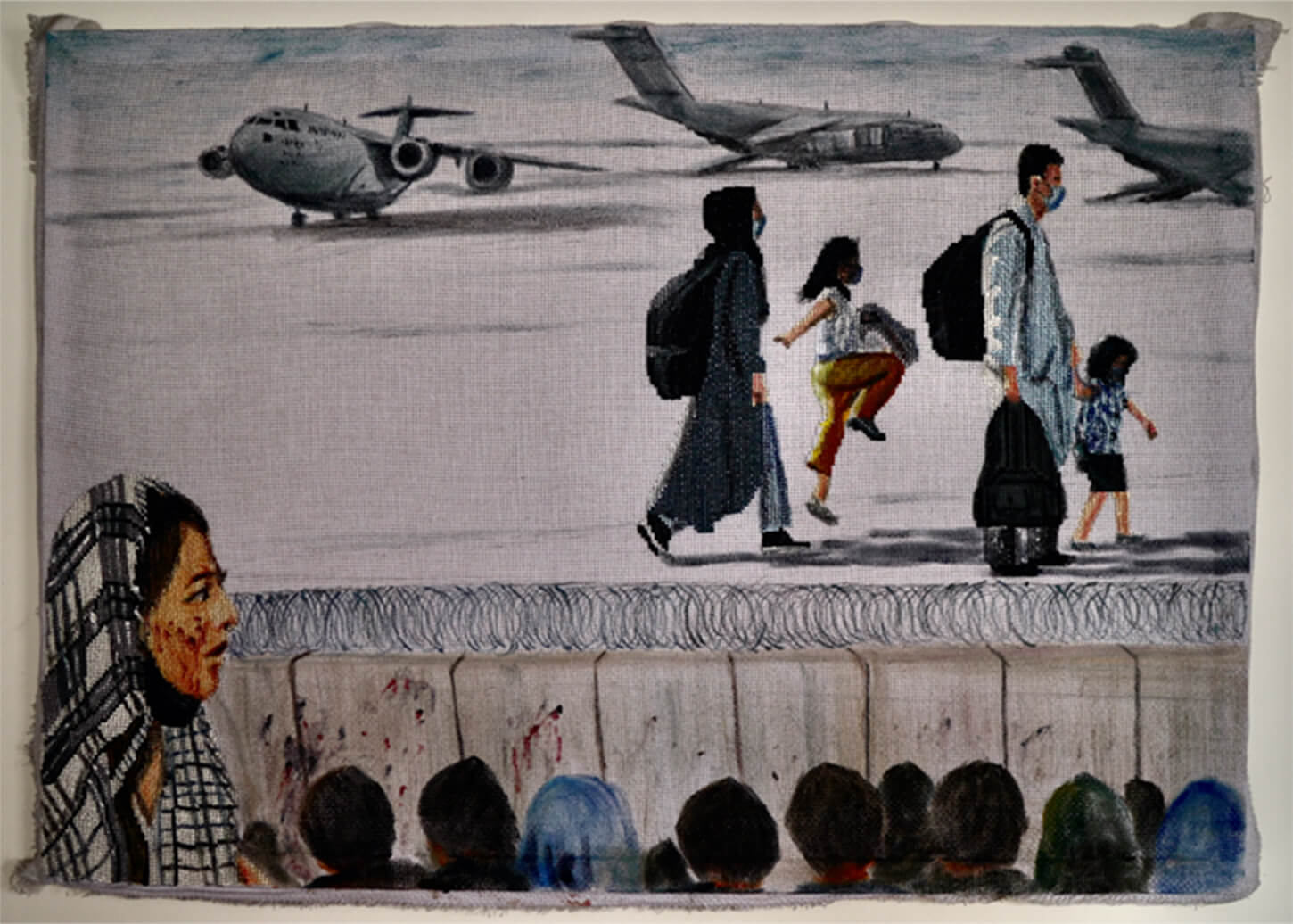

But her more recent work captures many of the changes of the past few months. There are tapestries depicting the evacuation of men and women from Kabul airport in the days following the Taliban’s arrival in the city. Others show women being stared at and women clad in burkas. Her work, she says, now focuses on the missing in Afghan society - those who left the country, the women who have disappeared from her neighbourhood, and those who never leave the house.

The evacuation of Kabul inspired Fatima's latest tapestries

Fatima used to teach other women to sew - women who, she says, were able to make good money from selling their work. But the Taliban view the tapestries as un-Islamic, and those women are now stuck at home.

“We were taking part in exhibitions within Afghanistan and outside - and we were making a profit,” Fatima explains. “[Those women] were the breadwinners of their families.”

Private spaces for women are vanishing. “I had a friend who I shared my life stories with - my secrets. But now she’s working in one hospital and I in another.” Fatima laments that they can no longer meet alone.

And she tells me how she went to the beauty parlour recently, only to find a picture of a woman which had been defaced - ink had been thrown all over it.

“I asked why the woman’s picture had been scratched out. They replied that the Taliban had warned them three times to cover it.

“I have cried a lot for the women and for that picture with the blotted-out face on the door of the beauty salon.”

Ameena

Intelligence officer, 29

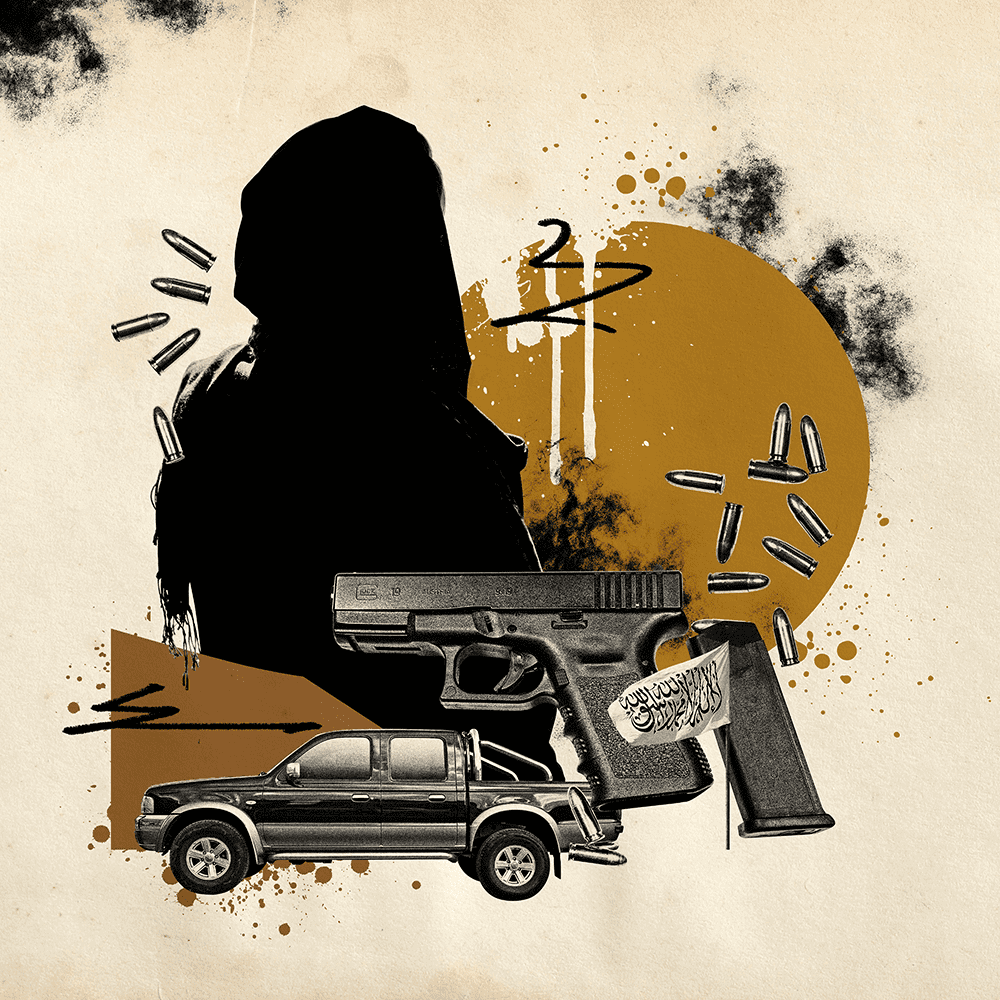

For 29-year-old Ameena, beauty salons are the least of her concerns. She says she is scared for her life.

On 15 August, she started the day by visiting a safe house belonging to the National Directorate of Security (NDS), the Afghan intelligence service. She had been pulling long days and nights, as province after province fell to the Taliban, bringing female agents back to what she thought would be the safety of Kabul.

There she gave them money and paid their expenses, before heading to the NDS headquarters on the road to Kabul airport.

The biggest pride for someone in the military is a weapon. It is very painful for us when a terrorist comes and disarms you

“I was able to secure the transfer of around 100 NDS female staff from across the country. It was totally unbelievable to me that Kabul would fall into the hands of the Taliban,” she told me over a cup of green tea.

“When I arrived at the office, I saw everybody upset and fleeing. I asked them where they were going. They said, ‘Madam, please leave the office - the Taliban have arrived.’”

But Ameena returned to her desk joking, that because of the bad Kabul traffic she didn’t think the Taliban would be able to make it to NDS headquarters until the next morning.

She says that, later on, human resources staff came to her and asked her what they should do as all the staff were leaving. “I asked them, ‘Where are all the officers?’”

She learned that they had all left - apart from two of the deputy commanders.

By around half past two that afternoon, Ameena left for home with an armed escort. She wouldn’t return to the NDS headquarters again.

Earlier she had watched President Ashraf Ghani flanked by his minister of defence and the head of the NDS issue an order that Kabul must be saved by any means possible. Now, at home, she saw on the television that the Taliban were inside the presidential palace. President Ghani, too, had fled.

Months later, she is still furious that he abandoned the country.

“It was his responsibility to resist until his last breath because he was the chief commander of the entire Afghan national security forces,” she says. “A person taking the lead of the security forces must not flee and must stand to the last drop of his blood - the final moment of his life in the world.”

The following days were a nightmare. The Taliban searched her home but she had already left in fear of her life.

The Taliban, she says, took her vehicle and a gun that she had left at home.

"The biggest pride for someone in the military is a weapon. It is very painful for us when a terrorist comes and disarms you."

Despite the Taliban’s steady takeover of the country, she believes Afghan forces were betrayed by politicians’ backroom deals. And perhaps in a state of denial, she hopes the West will again come to Afghanistan’s aid.

Afghan forces endured “a huge amount of casualties”, she says. “I felt like their sacrifice and the sacrifice of my close colleagues have gone to dust.”

She ends with a final plea to the US and UK: “The world and the international community must never forget our sacrifice, our endeavours and our efforts against the terrorist Taliban. And [not forget] the fact that we established a government over the past 20 years.”

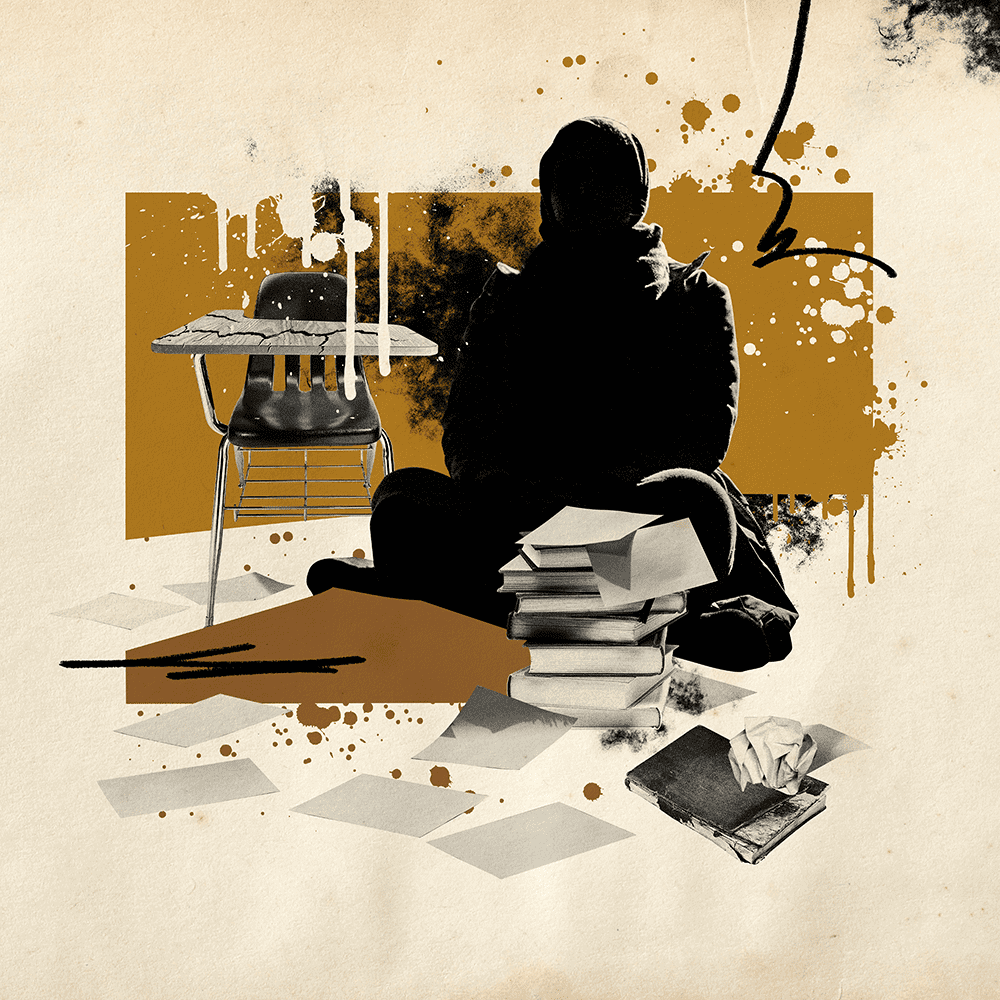

Mina

University student, 22

Mina makes no pleas to the West, except this: “Leave us alone,” she says firmly. After 20 years of Western assistance in Afghanistan, women’s rights were still under threat, even before the Taliban returned, she says.

Mina is a brilliant student, having finished near the top of Afghanistan’s “Kankur” national exams, through which 300,000 students apply for some 50,000 places at university. After four years of study, she was just one month from graduation when the Taliban arrived.

She says that “in a few hours” her future was altered. There would be no university diploma now. Mina had hoped to become a diplomat like others in her family, and perhaps study at Oxford. But serving Afghanistan was always going to be a priority.

“Without our education, our jobs are also under question and doubt. We don’t have bright prospects for our future,” she says.

Without our education, we don't have bright prospects for our future

Mina is quietly spoken but firm in her determination to succeed. The battle she describes to become educated, and independent, is not uncommon for Afghan women.

“When I was born, my aunties cried out in shock, ‘Why a girl!’” Mina is a reminder that even before the Taliban, Afghanistan came bottom of almost every index on women’s rights. She grew up during the democratic Afghan republic, but still she says she had to fight for every little freedom.

“Many people and relatives told me that law and political science is not good for girls.”

For Mina, and tens of thousands like her, all of those hard-won victories vanished overnight. Now she finds her world is much smaller. She spends most of her time in her room, working on her writing.

But the picture she paints is complicated. She says there is less harassment on the streets now that the Taliban, with their reputation for brutality and swift justice, are in power.

“One positive thing now is that we faced real problems on the street, many people used abusive words for girls, but now they can’t,” she says.

When I ask why, she replies that they will be punished.

But still she worries about going out. Many women say they fear they will be harassed at Taliban checkpoints for not being fully covered in a traditional veil, or for travelling alone without a male guardian. The Taliban have also been accused of searching women’s mobile phones for content they regard as inappropriate.

She still speaks to her friends, but mostly via chat apps on her phone.

And she hasn’t given up. Even as we sit there in a darkened room, with her identity obscured, she says she hopes not to be silenced.

“I want to serve my country and speak for my gender's rights. I want to fight for my rights, my generation's rights,” she says. “I think it's a pleasure to fight for our rights, to fight for my family, my colleagues and my friends. I'm able to raise my voice.”

Removing women from education will have long-term effects, but removing them from the workforce - as the Taliban have done in droves - is being felt immediately as Afghanistan faces its worst humanitarian crisis in a generation. Many women were the only breadwinners in their families.

Zahra & Samira

Police officers, aged 34 and 36

Zahra and Samira could star in their own buddy cop show. The two policewomen have known each other since childhood. They laugh and joke together and show me their target practice from the shooting range. Most of the shots are dead centre.

American funding greatly expanded the number of women serving in the police force and the military. But that money disappeared when the last US troops left.

Zahra remained at her post until the fall of Laghman Province east of Kabul. When the Taliban overwhelmed their forces, she thought about taking her own life.

“We don’t know whether we live in our own country or somewhere else,” she says. “It is extremely hard now. It’s as if I can’t breathe. My children were attending schools, courses and universities, but not now.”

I still stand ready to serve - I am waiting for that day to arrive

Zahra

She says the economic problems are getting worse by the day. “We’re stuck at home with no jobs and no earnings to support our lives.” And the women have lost more than just their incomes.

Nodding in agreement beside her friend, Samira says: “I used to solve the biggest challenges of my life, but not now. I could go to my daughter’s school and walk freely in bazaars. I had money, had the power to buy things, and could introduce myself to others with pride, but not now. I have lost my sense of self. There is no identity left for me now.”

Samira reflects on the days after the Taliban seized power - when she sat in a quiet corner of her rooftop in Kabul watching the planes ascend into the skies, taking thousands of her countrywomen and men to safety.

Zahra describes the months since then as if “black ink had been poured over white”.

The women are afraid. Suspicious when new people arrive in their neighbourhood. The Taliban claim to have offered an amnesty for those who served the former government. However, the UN says it has credible information that more than 100 people who served with the previous government have been killed since the Taliban takeover.

I used to have money, have the power to buy things, and could introduce myself to others with pride, but not now because I have lost my sense of self

Samira

Alia Azizi, a police officer and head of a women’s prison, has been missing for four months. She has not been seen since she was called to work by Taliban officials. A social media campaign #FreeAliaAzizi is calling for her release.

And four women who vanished with family members after attending a march for women’s rights in Kabul, were this week released. The Taliban consistently said it did not have the women. It also says it is not holding Alia Azizi.

Zahra says because of these fears, her children say they wish their mother hadn’t served in the security services.

“I tell them it is OK and I hope one day they will know that we have offered great services by sacrificing our lives, putting ourselves in huge danger and still standing ready to serve. So I am waiting for that day to arrive.”

And she adds, “America and Nato encouraged us to take these jobs. We had training from so many ladies from America, Canada, Germany, Holland, Poland and a great many other countries. They said they would stand beside us - shoulder to shoulder - but in the end they have left us alone, abandoned.”

Other than Fatima, the names of the women we spoke to have been changed to protect their identities.

Judges hunted by murderers they convicted

Judges hunted by murderers they convicted

Return to Afghanistan

Return to Afghanistan

Rural family welcomes Taliban rule

Rural family welcomes Taliban rule