The doorbell rings at 10 Crescent Road around 7pm.

It’s a Sunday night in November and inside the grey, stone Victorian villa Veronica and Alistair Wilson are getting their young sons ready for bed.

Alistair - or Al, as he's known to friends and family - has just settled down to read to the boys, one balanced on each knee.

Veronica is also upstairs, sorting out the laundry.

The Wilsons have had a busy weekend catching up with friends at their home in Nairn, a seaside town in north-east Scotland.

They are also looking after another friend’s 18-month-old and, when the doorbell goes, they assume his parents have come to collect him.

Usually they come in through the back door, but Veronica thinks it must have been accidentally locked and goes downstairs to let them in.

But standing on the doorstep in the darkness is a man - a stranger who simply says two words: “Alistair Wilson”.

Despite her surprise, Veronica doesn’t feel particularly uncomfortable. In fact, she doesn’t even close the door on the man as she heads back upstairs to fetch her husband.

She assumes the visitor has something to do with Alistair’s job as a banker.

As her husband leaves the comfort of the sofa to go to the door, Veronica takes over the boys’ bedtime story.

About 10 minutes later three gunshots ring out.

Over the past 13-and-a-half years, fresh leads have emerged in the case of the doorstep murder, but no-one has been arrested. Why has the case of 30-year-old Alistair Wilson become one of the most baffling of recent times?

It is a hectic weekend for the Wilson family. And with Christmas on the horizon, the house is messier than usual.

“Al, in all his wisdom, had invited our friends to stay, not remembering that the spare room was covered in Christmas,” says Veronica.

“On Saturday we were focused on tidying and clearing away Christmas wrapping as much as we could. Al was cleaning downstairs, I’m cleaning up and we’re swapping over, passing each other on the stairs.

Our friends arrived by teatime, we put all the children down to sleep and caught up with them. We had a nice evening.”

On Sunday, the two fathers go trekking in the woods with the older children, while the mothers take the younger ones to a play centre. They all meet up for lunch, before saying goodbye around 3pm.

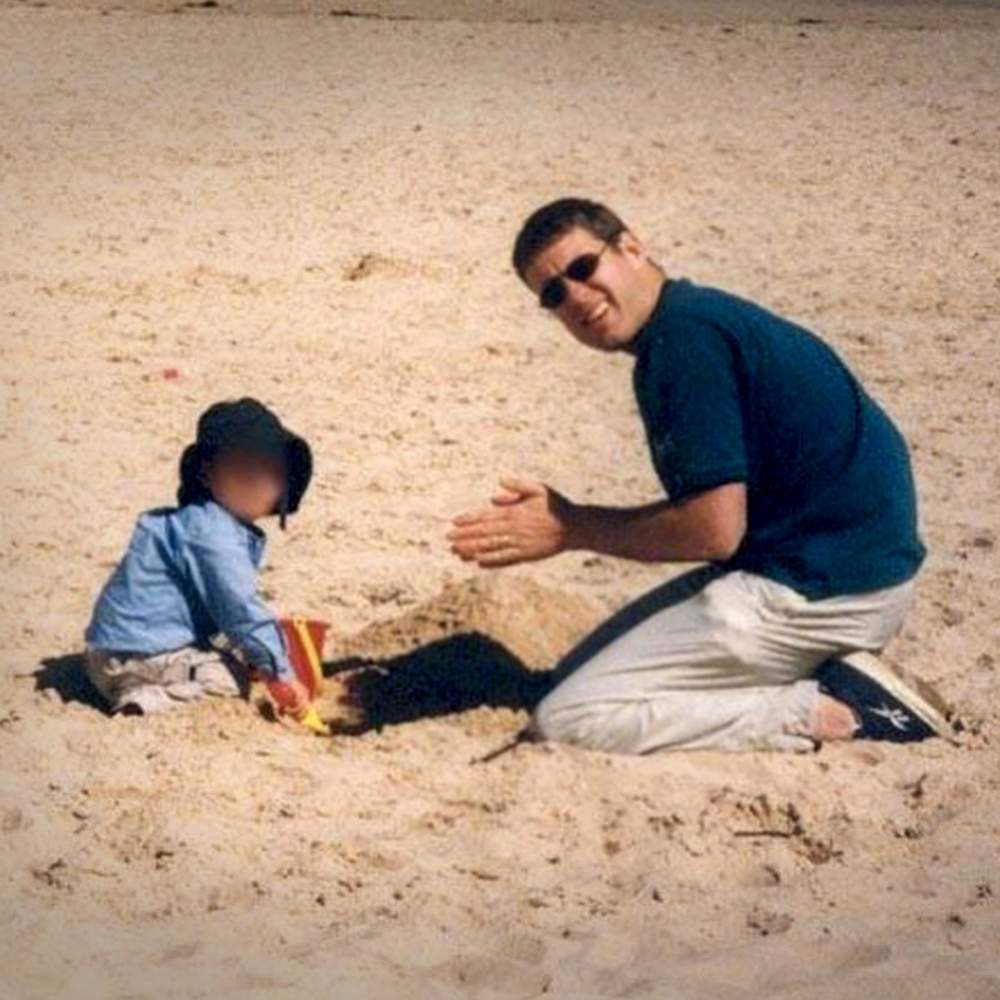

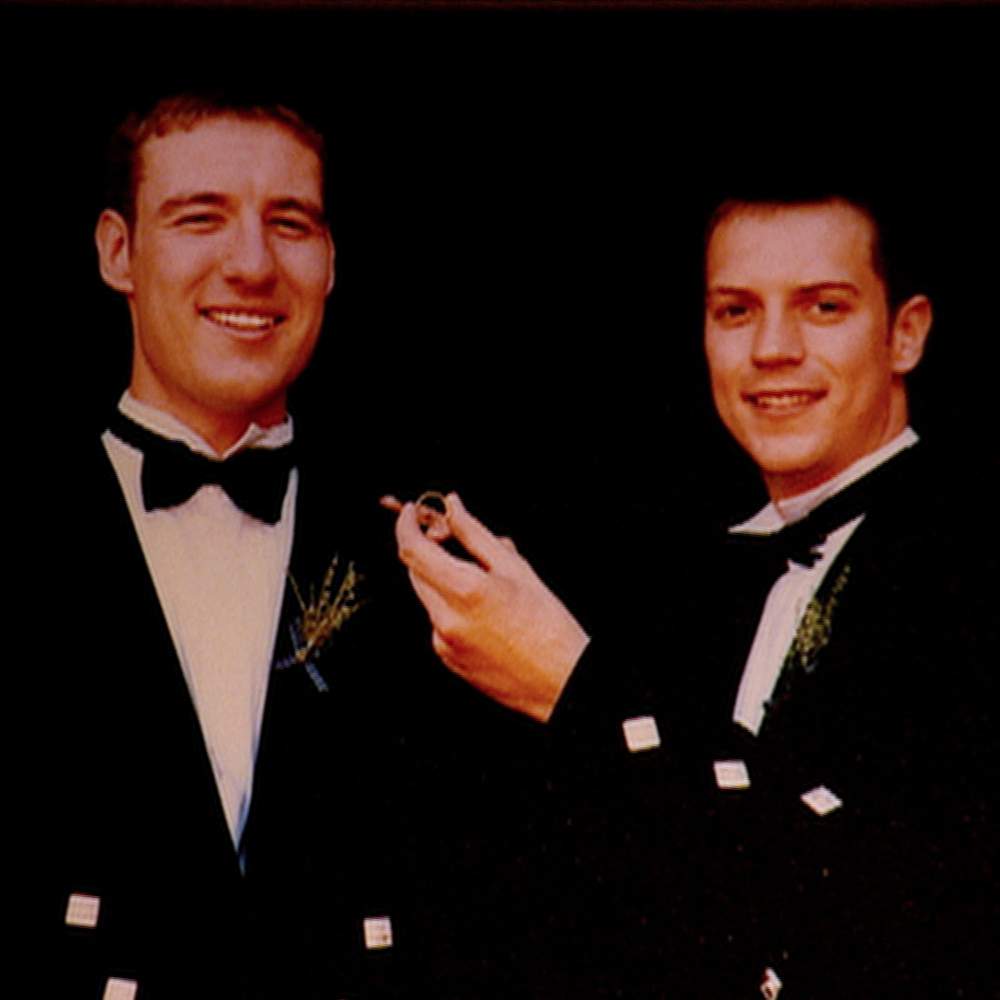

A photo of Alistair Wilson taken on the day he died

The remainder of that day will be familiar to many families across the UK. Alistair and his eldest son go to the supermarket to pick up something for dinner. They drop off the recycling and wash the car.

Veronica’s father Ronnie is staying in a flat at the top of the large, two-storey home. They all enjoy an evening meal together - just like any other Sunday.

That was 2004. Veronica and Alistair had been married for six years and were moving into a new stage in their relationship. Their two-year-old was in playgroup, and the four-year-old had started school a few months earlier.

The couple had a bit more time to spend together, and had recently gone to the cinema on their own for the first time since their eldest was born.

Theirs had been a whirlwind romance, which saw them engaged within six weeks of meeting through mutual friends.

Veronica was a graphic designer from Fort William, 80 miles (128 km) from Nairn. Alistair had been dispatched to the west Highland town in his first posting for the Bank of Scotland, after graduating from Stirling University.

“He was one of those people you met and you just knew,” says Veronica. “It all happened very fast.”

Alistair was a genuine, honest man, she says. “When he said he’d be there at 8 o’clock, he was there at 8 o’clock - with a bunch of flowers. It was very nice having somebody who just instantly cared so much.”

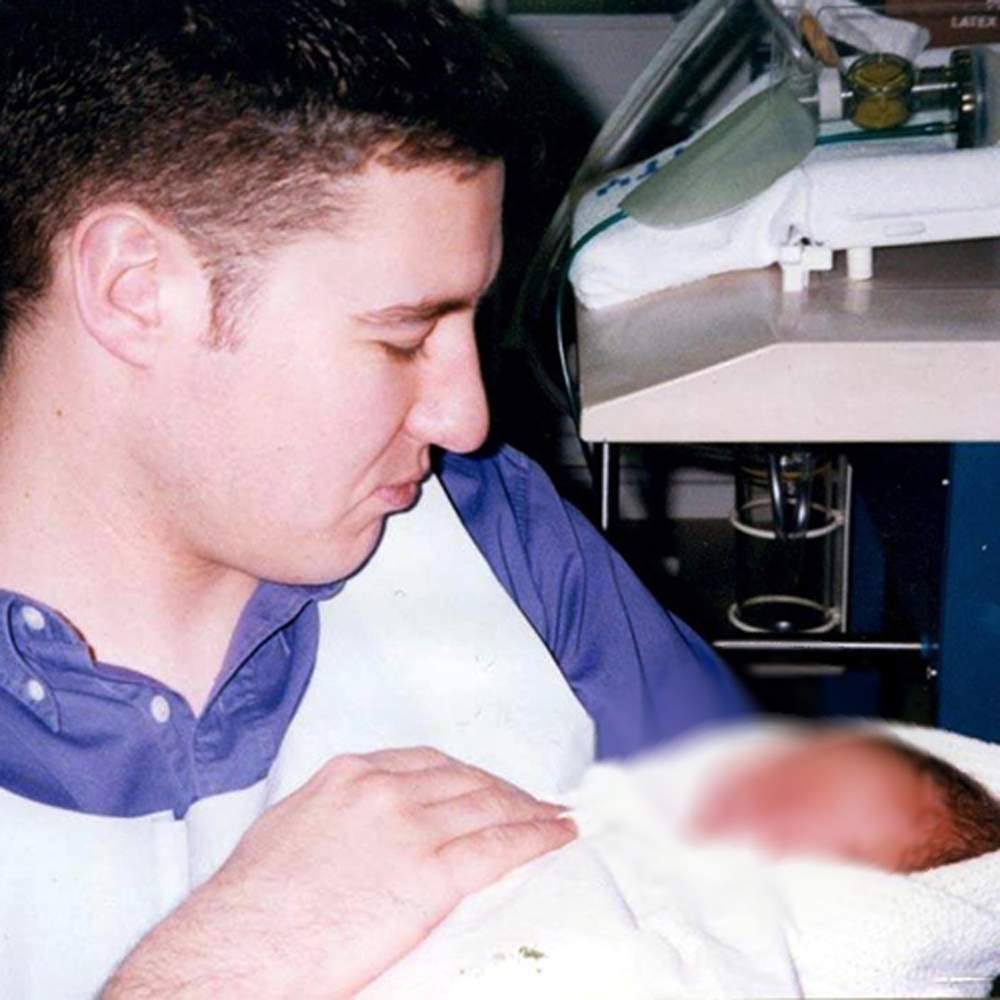

Golf was Alistair’s other love when he and Veronica got together. His priorities changed, however, when the children came along - hobbies fell by the wayside and his focus moved to being a hands-on dad.

Weekends were no longer spent on the golf course but as a family on Nairn’s beautiful beach and bandstand, which the family home overlooked.

They had been living in the town for 18 months, but even before they made it their home they would spend weekends there.

It’s a place synonymous with natural beauty, sandcastles and ice-cream. Sleepy Nairn couldn’t be further removed from a gangland-style execution.

The Wilson family home stands in the middle of a quiet street tucked behind the main road. There are steps leading up to it and no hedges, so the front door is visible from the street.

On the night of 28 November, two people standing on the opposite side of the road see two men talking at the door. They don’t see the visitor’s face.

Veronica, however, remembers the stranger as white, stockily built, with a dark baseball cap pulled down over his face. She says he was clean shaven, wearing a dark blue bomber-style jacket and dark jeans. He was 35-to-40-years-old and 5ft 6ins to 5ft 10ins.

The exchange between Alistair and the man is believed to have lasted a couple of minutes, and when Alistair goes back into the house, he closes the front door behind him.

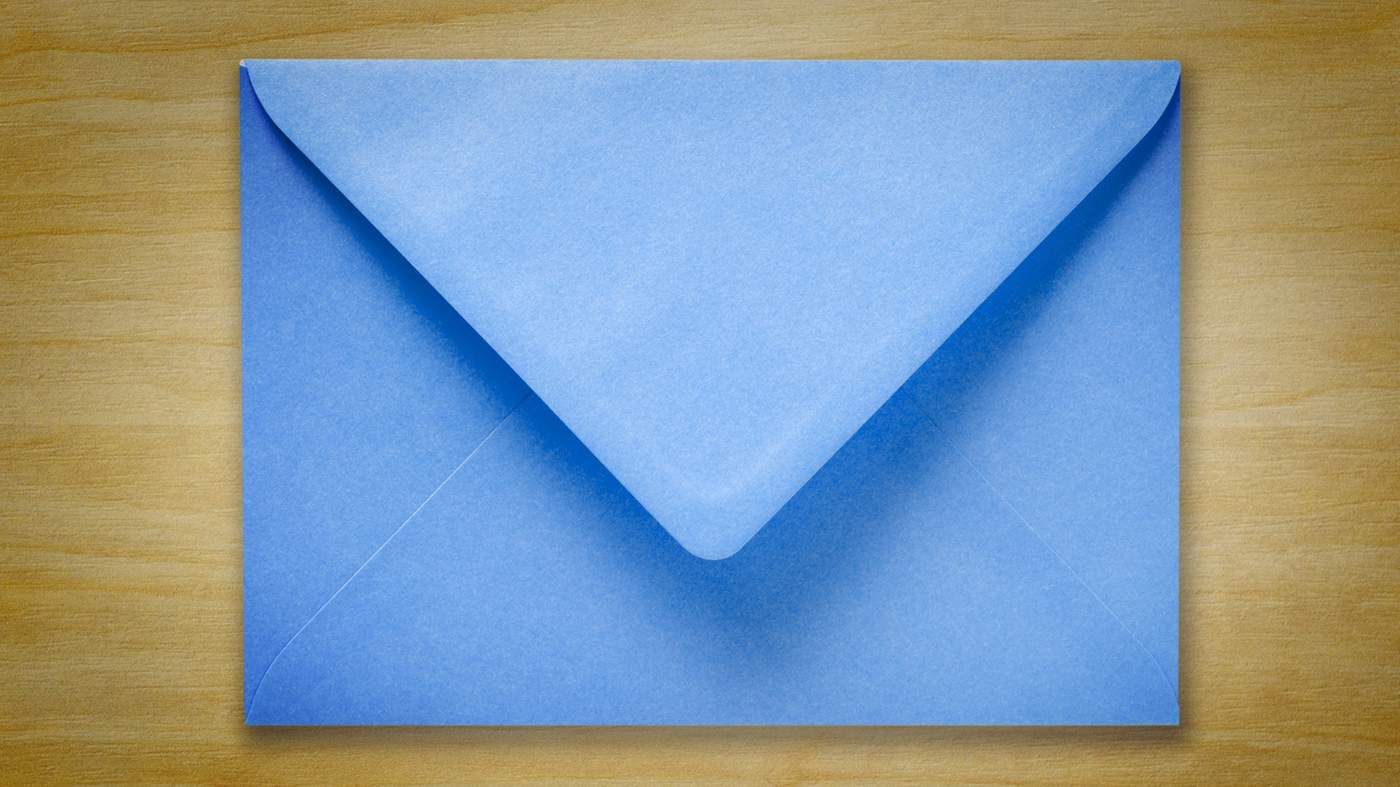

Veronica remembers him returning to the boys’ bedroom carrying a bright blue envelope. It’s the type that comes with a birthday card - a quarter of A4 in size and made of good-quality paper.

Written on the front of the envelope is the name Paul.

“[Alistair] was just a bit bewildered as to what the gentleman had said, because the envelope wasn’t addressed to him,” says Veronica.

She tells her husband that the man had definitely asked for him by name.

Even stranger, she says that when Alistair shows her the envelope, it was empty.

“He was puzzled, but no fear - the door is closed, we have a phone right next to us, and we have my dad on the top floor,” says Veronica.

He had options to take, if he felt any danger. I felt he didn’t feel uneasy at all.”

The couple discuss the situation calmly; they talk about putting the boys to bed and then trying to figure out what was going on. But Alistair insists on going back down to see if the man is still there.

“There was no fear, otherwise I wouldn’t have let him go back downstairs,” she says.

The man is still standing on the doorstep. Moments later, Veronica hears a loud noise. Her first thought is that wooden pallets have fallen to the ground.

Then she is up on her feet, running down the stairs.

“I don’t know what I’m expecting to find," she says. "Al’s lying there. I think he’s been hit, you know, the guy’s punched him.

“I ran over, and he’s covered in blood.”

Alistair has been shot at close range - twice in the head and once in the body.

He is still breathing but barely conscious, and losing a lot of blood.

From the porch Veronica sees her husband’s killer leave, heading down Crescent Road to her left. He is walking.

Alistair dies an hour later in hospital.

But what has become of the blue envelope he had been holding just minutes before he was shot?

It hasn’t been seen since, and there have been no end of theories as to what part it might have played in the murder.

Why was Alistair handed the envelope and allowed to return to the safety of his house - rather than being shot when he first came to the door?

Maybe the envelope was some kind of demand. Was Alistair supposed to put something in it?

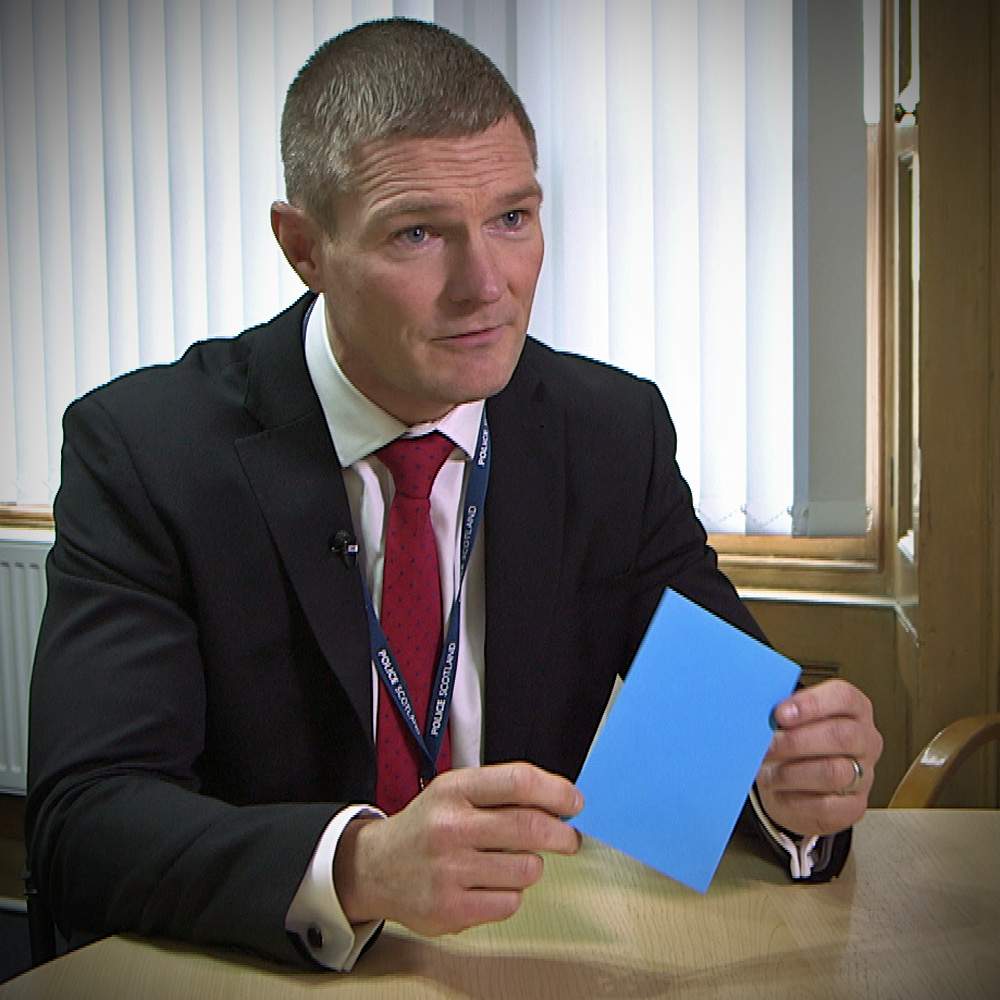

Det Supt Gary Cunningham, of Police Scotland's Major Investigation Team, holds an envelope similar to the one handed to Alistair Wilson

The killer appears to have wanted Alistair to take in the circumstances of the envelope, or wanted him to show it to Veronica – or both.

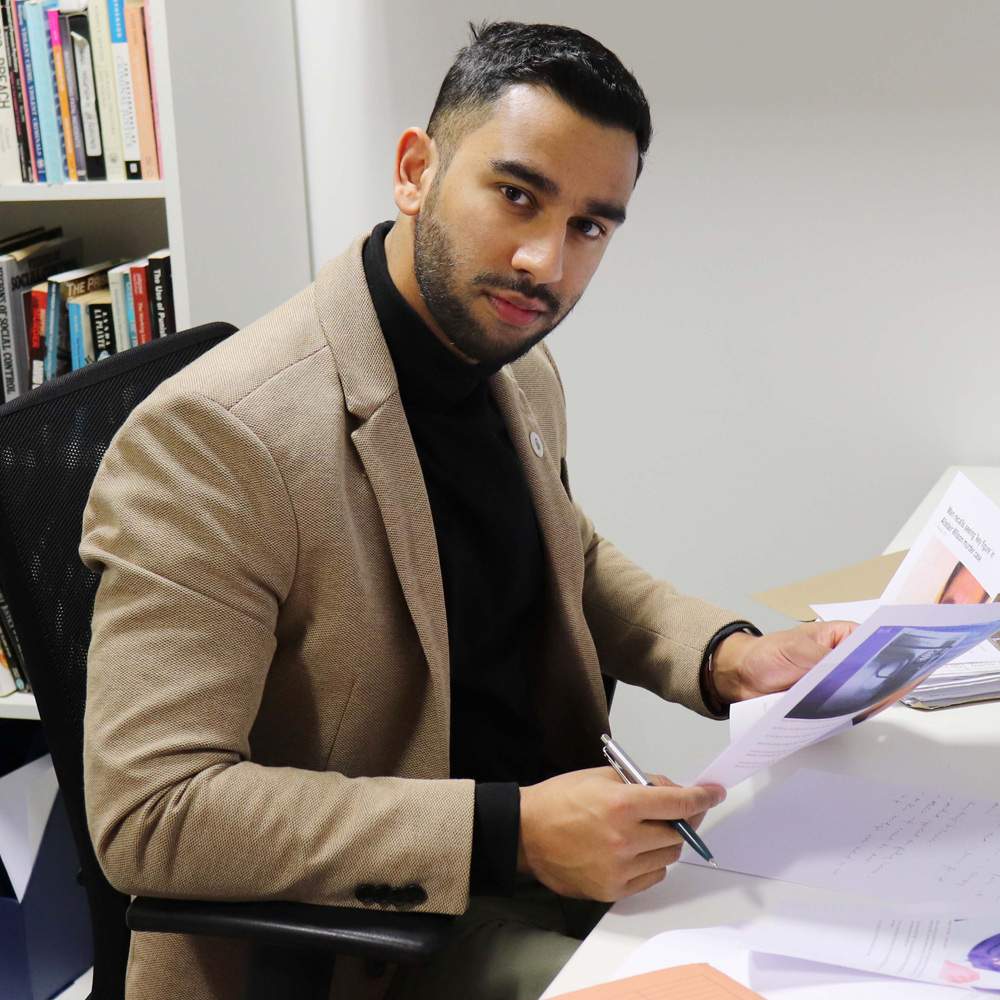

Birmingham University criminologist Dr Mohammed Rahman has examined the events of that November night.

“I believe that there is some substance to the name Paul,” he says.

“It could’ve been related to Alistair’s work, it could’ve been a pseudonym for a person, or a project that he was working on, or an abbreviation of something that only Alistair knew of.

I believe that the symbolism of the envelope is important. Envelopes are used to send a message to people.”

Dr Rahman suggests that whoever wanted Alistair dead wanted the name Paul to be circulated in the media, sending a message to others.

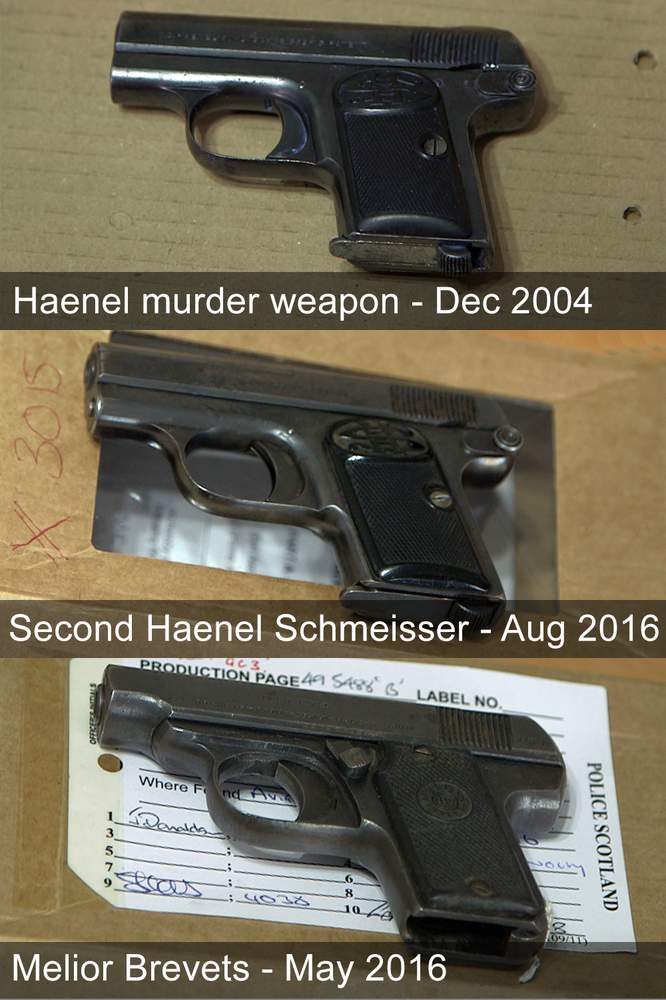

But the envelope is not the only piece of crucial evidence. Ten days after the murder, an antique gun is discovered not far from the Wilson’s home.

It is nearly 3pm and council worker Andy McMann is nearing the end of his shift. He and his colleague are on Seabank Road in Nairn.

It’s a wide residential street framed by impressive detached and semi-detached houses with colourful, well-tended lawns and pretty guest houses.

A gully cleaner has just finished unblocking a drain outside the first property on the street, near the junction with the main road and opposite an imposing Victorian-era Church.

Andy arrives 15 minutes later and is cleaning around the drain. He looks into it, making sure no tar has fallen in. Something catches his eye.

Council worker Andy McMann found the murder weapon down a drain

“There was a gun just sitting at the bottom of the drain,” he says.

“First of all I thought it was a dummy gun because of the size of it, it was tiny.”

It’s a Wednesday in December 2004 and the brutal murder of Alistair Wilson half a mile away is fresh in Andy’s mind - as it is for many of Nairn’s 11,000 residents.

“With it being down a drain, I thought it was somebody playing a sick joke, after what had happened,” he says.

The same make of gun as the one used to kill Alistair Wilson

Andy asks his colleague to fetch him a double-handed shovel, then he lifts the grating and, wearing rubber gloves, carefully retrieves the gun from the drain. It is wet and muddy and its heaviness surprises him.

“It wasn’t until I got the gun out and I felt the weight of it, I realised it wasn’t a toy one,” he says.

Andy puts it on the pavement and covers it with a traffic cone while the police are called.

Days later, tests reveal that the antique handgun is the weapon that was used in the murder of Alistair Wilson.

It’s a 1920s Haenel Schmeisser semi-automatic, nicknamed a “pocket pistol”.

Months after Alistair’s killing, the police investigation into his murder was dealt a huge blow when no identifiable DNA was found on the gun.

But a 20-strong team of officers are now reinvestigating the case, and the gun and a cigarette butt found on the Wilson’s doorstep are being put through more advanced testing, called DNA24.

Forensic scientist Joanne Cochrane

Joanne Cochrane, the team’s forensic scientist, says: “The main improvements in the very latest technology are increased sensitivity.

“Fourteen years ago we were using a different DNA profiling kit that only looked at 11 areas of DNA. We’re now looking at 24 different areas of DNA.

“The potential for every cold case is extremely exciting.”

DNA is one of many avenues that police are pursuing. Another lead arose because of a phone call to the BBC.

John Beattie is on air when the call comes in.

The former international rugby player, accountant, and now presenter for BBC Scotland, is working on his lunchtime radio programme.

It is 28 November 2016, the 12th anniversary of Alistair’s murder.

Over the years, teams of detectives have combed through the banker’s private and professional life.

John has just interviewed criminologist Professor David Wilson, who said the key to the case was the blue envelope.

A message appears on the presenter’s computer while he’s in the studio.

“A producer told me someone had phoned in to say they thought they knew what had happened with the murder,” John says. “They had left a number.”

It was the reporter’s relationship with the police that culminates in new evidence being revealed to the BBC. This includes the fact that the envelope Alistair was given was empty, and the revelation that other guns had been found in Nairn.

During her interview, Fiona asks Veronica whether the claims made by Peter sounded plausible.

“No,” Veronica says. “But equally, neither does the scenario of that night, so I appreciate everything needs to be investigated and people will have different ideas on it.

It doesn’t sound anything like our life. But if you’d told me that somebody would shoot my husband on our doorstep while we were all in the house, I wouldn’t have believed that either.”

The man leading the police inquiry, Detective Superintendent Gary Cunningham, confirms Peter’s allegation was one of the investigative strands his team were progressing.

He says they took a statement from the big businessman Peter had spoken about. But he wasn’t interviewed as a suspect because there are no suspects.

Fiona has now produced a podcast called The Doorstep Murder, which sifts through the details of the case.

It looks at various theories, from mistaken identity to Alistair’s job at the bank, which he was due to leave two weeks after he was murdered.

The person closest to Alistair still lies awake at night wondering why her husband was gunned down.

“You can’t not,” Veronica says. “It’s never away – it’s just filed in places.”

Alistair and Veronica’s life have been looked into, in fine detail, over and over again, by different police teams. There is nothing that hasn’t been touched.

Amid all of that scrutiny, Veronica is certain there is no dark secret in her husband’s past.

She’s convinced that had Alistair survived, he would not have been able to tell her why he had been targeted.

Veronica says she knew him inside out and feels that if there had been a secret, she would have known about it.

Then there was Alistair’s behaviour on the night he was killed. Surely, she says, if he had felt any danger when the stranger turned up on the doorstep, he would have protected his wife and children.

Why would he have gone back downstairs if he felt threatened?

“The only thing that makes any sense to me was that it was the wrong Alistair Wilson,” Veronica says.

This is a theory that hasn’t been ruled out by police, despite having spoken to a number of other Alistair Wilsons in the Highlands and across Scotland.

“We have to look at personal, we have to look at professional, we have to look at associations, and we have to look at possible mistaken identity,” says DS Gary Cunningham.

There was another Alistair Wilson in Nairn, just a few minutes’ walk from where the family lived in Crescent Road. He was in his 60s and died at the end of last year.

A neighbour said he felt uneasy about sharing the same name but couldn’t think of any reason why he would be a target.

When asked if Alistair was in debt or any kind of financial trouble, DS Cunningham simply says: “This is still a live investigation; I can’t go into that detail.”

Criminologist Dr Mohammed Rahman says like the criminal underworld, the corporate world is motivated by the acquisition of power and profit.

Criminologist Dr Mohammed Rahman

“The difference is that within the underworld, criminals take an alternative approach to justice, which is murder.

“There’s a variety of things that can get someone killed within the criminal underworld. The common ones tend to be business deals gone wrong, extortion, dishonour of a criminal fraternity, elimination of competition, or members of a rival group.

“Alistair worked for a bank. He worked in finance, which is a very aggressive and competitive market.

If there is any substance in relation to Alistair and connections with the criminal underworld, I strongly believe that it’s linked to his workplace, or his previous employments.”

DS Cunningham says gangland links have to be a focus of his investigation – not the focus but a focus.

Organised crime has come up repeatedly, and he says police can reassure anyone who comes forward that they can be protected – they have a unit for this very purpose.

There are people out there who know the exact motive, the detective says. People who can tell a family why their loved one faced a brutal execution on their doorstep.

For Veronica Wilson, the death of her husband dominates her thoughts. The family exists rather than lives, she says.

And another thing she has had to contend with is the finger of suspicion pointing closer to home.

The aftermath of the shooting is a scene of chaos.

After finding her husband on the floor in the porch, Veronica is hysterical.

She is on the phone to the emergency services, while trying to stem the flow of blood from her husband with towels.

Several people run across the road from the Havelock Hotel. Some are kneeling beside Alistair, talking to him - trying to reassure him. Others are attempting to clear the space around where he has fallen.

As Alistair is dying in the doorway, his eldest son comes out of his bedroom and sees his father lying there.

It is not a place that is used to violent crime. Nairn is a well-heeled coastal resort with a reputation for good weather - or at least for the north of Scotland.

Before Alistair was shot, the last murder there was in 1986, when a man was killed after an argument at a wedding reception.

Nairn has an air of grandeur, but it’s not a stuffy place. People won't turn heads at either full-tweed stalking gear or a tracksuit. You walk down the main streets and you still hear the seagulls - past bakeries, pubs, chip shops, a wool shop, a flower shop and a bookshop.

Come the summer and the noise of the gulls competes with the pipe band.

There is a highland games and an annual agricultural show. There is a caravan park and a bandstand with views across the beach out to the Moray Firth. You can take a boat cruise and go dolphin spotting. This is the Highlands but with an airport 10 minutes away.

So has this picturesque seaside town, a proper old-fashioned community with a low crime rate, been changed by one act of incomprehensible brutality?

“I think it made Nairn a very sad place [at the time],” says a woman sitting at the bar of one of the local pubs. She knows the Wilson family but doesn’t want to be named.

She says that after the killing some locals would be watching their back if they were out in the evening - but added it was “totally unnecessary because it was a one-off”.

“I think we picked ourselves up quite well from it all,” she says.

We have a beautiful town and the Wilson family home looks out beyond the bandstand and a beautiful beach.

“I think the family take a great deal of comfort from where they are and their surroundings.”

Regarding Veronica’s decision to stay in the house, the woman says she “takes her hat off to her”.

“It was a big decision for her to stay there. She’s very hardy. But I can understand why – happy memories she’s had there and her children having happy memories with dad there.”

But the fact that no-one has been caught has left the “close knit community” needing closure, the woman says.

“We need to know for the family why this happened.”

Local window cleaner Mike Squirrel says: “It filled our minds for a long time; concern about the family, thinking that if someone like that is around in Nairn, could it happen to someone else? I would say it had a massive impact on us.

“There’s no closure, is there? It’s one of the weirdest cases. And up in the Highlands, murders are nearly always solved.”

The police have said Veronica is not a suspect. But while the murder remains unsolved, suspicion has fallen on her in some quarters, a fact that she’s all too aware of.

“Now that my children are becoming adults, I just don’t want them to have the life that I’ve had to lead, knowing that people are talking about you,” she says.

“I always try to put myself in their position - what would I think if I read about us? And I do believe that to be able to sleep at night, people have to think that there was something there, but it just makes our life very uncomfortable.”

Why would she leave her children without a father, she asks. Why would she have him brutally murdered at the family home, when their boys are there?

For Veronica and her sons, life passes, but it's not really living.

"For us as a family, we need to know why,” she says.

“This is just so senseless. Our life just won't ever be anything without answers."