Will Finland's basic income trial help the jobless?

- Published

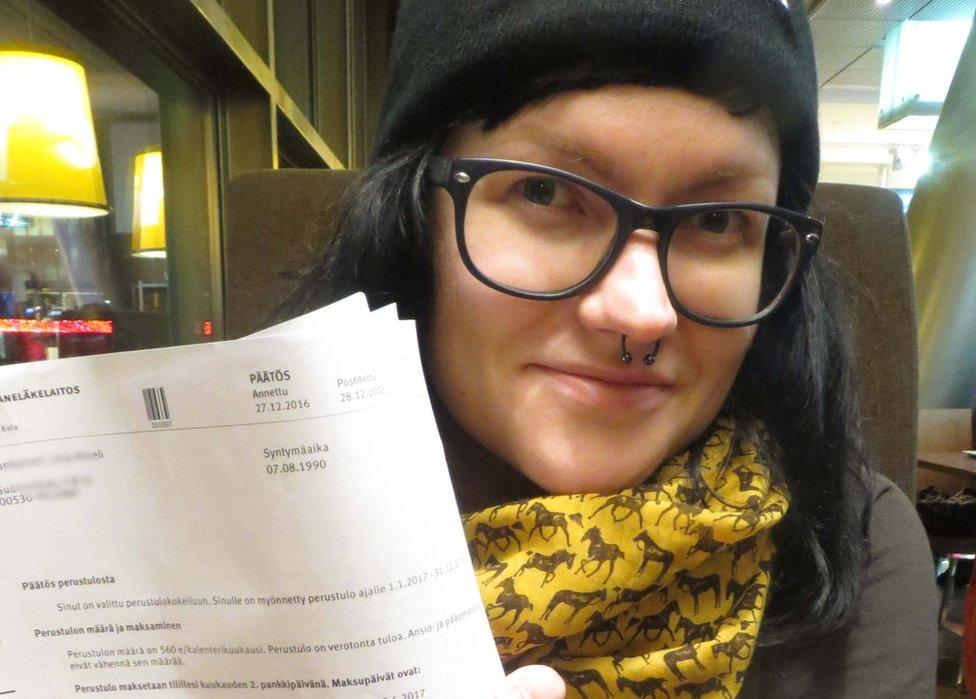

Liisa Ronkainen likes the idea that she will continue to receive the basic income even if she finds a job

"I was so surprised when I got the letter, and a bit sceptical too," says Liisa Ronkainen, one of 2,000 Finns chosen for a government experiment to provide unemployed people with a basic income.

Out of work for half a year, Liisa, 26 and from Helsinki, has been looking for a job without success.

"While I'm unemployed I will only get €36 more per month with the basic income. I've always been positive about the idea, though, so it was nice to be one of those who were chosen."

Basic income has frequently been suggested as a way of cutting welfare bureaucracy as well as poverty.

But one of the main reasons why Finland's social insurance agency Kela is trying out the monthly tax-free payment of €560 (£490; $600) is to see whether providing a basic income will make the unemployed more eager to go into short-term jobs.

Finland has some 213,000 unemployed, a higher rate than its Nordic neighbours, and a working population of 2,413,000. Short-term contracts here have steadily become a key feature of Finland's labour market.

The benefit system in many cases provides people with little incentive to go into low-income jobs because welfare is generally cut back if you start earning.

"Every single euro that a person earns diminishes his or her social benefits," says Olli Kangas, head of society relations at Kela.

"In some cases an unemployed person is afraid of losing their benefits in the future, if he or she receives a temporary employment."

Olli Kangas sees the two-year trial as merely the start of Finland's experience of basic income

The idea behind the basic income experiment is that any earnings would be a supplement; €560 a month may not sound much but it is a start.

"The government wants to see if it's possible to eliminate at least the worst disincentives to work," says Mr Kangas.

Where else in the world?

Swiss voters overwhelmingly rejected paying all adults a basic income in June 2016

Four Dutch cities - Groningen, Tilburg, Utrecht and Wageningen - are to take part in a trial

The Canadian province of Ontario will hold its own experiment

Scottish councils in Fife and Glasgow may also stage a trial

Randomly selected from Finland's unemployed, the 2,000 taking part in the experiment were all receiving the lowest rate of unemployment benefit. After tax, it was little different from the €560 they now receive monthly in basic income.

The difference is that they will receive it without filling in a form and irrespective of whether they get a job or not over the next two years.

For Liisa Ronkainen, already looking for work for several months, it is certainly an attractive idea.

"Now that I will get a salary in addition to the basic income I might try even harder," she suggests.

And there was a similar message from another of the participants, Juha Jarvinen, who has been out of work for five years but now hopes to start a new business. "For my part, the basic income will mean I can escape enslavement and feel that I am a functioning citizen again," he told Finnish public broadcaster YLE.

The trial has aroused interest worldwide, because it will answer the burning questions about how people out of work will respond to the idea of a basic income.

Some might decide to acquire more education or change their career, to make themselves more attractive to the labour market. Others might seek to start a business.

But there is always the chance that it could be used as an excuse to take it easy and work as little as possible.

Cutting bureaucracy

None of those chosen was given a chance to say no, so the outcome of the project will not be slanted. And no-one will receive less money than before.

As for cutting red tape, the prime objective behind the pilot, there will be a partial improvement for those taking part.

Those selected for the trial by Kela are aged 25 to 58

Most of those involved receive additional social benefits in the form of housing benefit or a higher unemployment benefit because they have children. The form procedure to get these will remain unchanged during the experiment.

But for Finnish authorities bureaucracy will diminish considerably. If any of the 2,000 start studying, get a job or lose a job or even develop a long-term illness, they will not have to pass the information on. Their basic income will not change.

More stories from Finland:

As the experiment takes hold, researchers will watch how the chosen group fare in comparison with the rest of the country's unemployed.

They have already suggested expanding the experiment, either to increase the number of unemployed people taking part or to widen it to other groups in society.

The Finnish centre-right government of Prime Minister Juha Sipila has provided €20m to the project and the research group says most of the money will remain untouched until the start of 2018.

"This is just a start," says Olli Kangas. "In 2018 we would like to start something better."

As for the cost of the experiment, that depends on how many of the 2,000 will find work.

The basic income will initially be covered by the money that would have been paid out in unemployment benefit anyway. Costs will only start to build up when people get a job.

- Published5 June 2016

- Published30 November 2016

- Published25 November 2016

- Published1 February 2016