Detroit City FC: The football team rising from America’s biggest ruin

Last updated on .From the section Football

Trevor James has seen a lot in his footballing life.

In the 1980s, he played for the LA Lazers, a short-lived indoor soccer cousin to the famed LA Lakers, attracting a similarly glitzy Hollywood crowd to the city's Forum arena.

In the 1990s, as part of Sir Bobby Robson's scouting network, he picked apart England's World Cup 1990 opposition before being deployed to watch Brazilian phenomenon Ronaldo in preparation for Barcelona's then world-record £13.2m purchase.

In the 2000s, the arrival of David Beckham transformed the LA Galaxy team he helped coach from global non-entity into a travelling circus.

He has even barked orders at the likes of Rod Stewart, Ronnie Wood and Andrew Ridgeley as manager of Stewart's LA Exiles - a team of ex-pat musicians, actors and artists who have made California home.

But he has never seen anything like Detroit City.

"It is a unique club," he tells BBC Sport.

"There is a mentality that is Detroit against the world. They want independence because that is what Detroit is. Detroit City FC is an independent club.

"Some really good things come out of that. And occasionally we'll do things that upset people."

"People are desperate! There's no work out there, man; they're selling everything! It's down to a dime on the dollar."

That was how a hitch-hiker described the situation in Detroit to journalist Hunter S Thompson in his 1972 book Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail.

Nearly half a century on and now Detroit's demise is news to no-one.

The journey from the richest city per capita in the whole United States in 1960 to the largest municipal bankruptcy in the country's history in 2013 was propelled by the decline of the American car industry, as jobs, people and money - public and private - haemorrhaged away.

In many parts all that was left behind was a mausoleum to America's motor age.

In the depths of that depression, one of the few modern growth industries involved sightseeing tours to Michigan Central Station, whose vaulted marbled ticket halls lie strewn with rubble, or the United Artists Theatre, an elaborate 2,000-capacity Gothic- style cinema that sits silent and sunlit through a shattered roof.

Perhaps most poignant were the everyday scenes; libraries lined with books, classrooms filled with desks and police stations with evidence still pinned to the walls - everything essentially in place, but long devoid of human life.

Keyworth Stadium could have gone the same way. President Roosevelt opened it in 1936, promising it would "last for many years" as his nation attempted to lift its sights from "bare food and lodging" to "enjoyment and recreation".

By 2015 the grandstands sagged, the locker rooms needed repair and the floodlights were broken. It has had an unlikely saviour.

On a chilly evening last October, a 1,000-strong mob, many clad in black, collected outside a bar on Christopher Street half a mile away from the stadium. Among their number were some of the hundreds who had raised $741,250 (£594,000) as part of a community investment scheme to renovate Keyworth. They had dedicated their time and money for evenings like this.

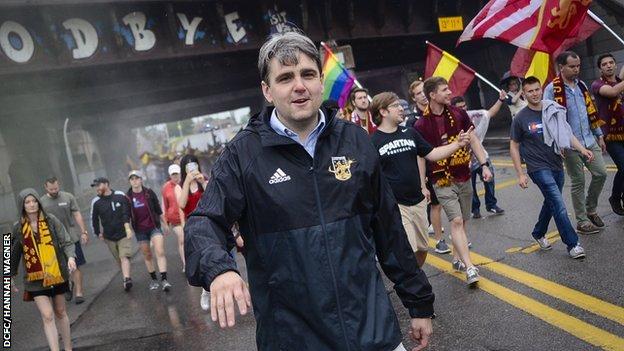

Together, with gold and maroon flags hoisted aloft, they marched to watch Detroit City play Milwaukee Torrent and lift the NPSL Members Cup.

In total, the crowd numbered 5,720. That is an entirely usual gate for Detroit City, but utterly unprecedented numbers for the fourth tier of American soccer, where attendances are often in the hundreds.

For reference, their average crowd last year would place them comfortably in the top half of the second-tier USL Championship and was greater than plenty of clubs in England's League One drew last season.

The volume of people is one half of the story, though. The other is the volume of their support.

Detroit's own chief executive Sean Mann describes the club's fans as "rabid and notorious". And he means it entirely as a compliment.

For while Mann and four friends founded the club in 2012 - after long nights drinking and deliberating in a basement bar Mann designed around a Bristol boozer he frequented during his time studying for a degree in the UK - it is the fans on the stands who have since defined its identity. It began before the team had even set foot on the pitch.

Brothers Ken and Gene Butcher - long denied an outlet for their football passion - appeared at Detroit's first try-outs armed with flags, drums, smoke bombs, a few friends and a determination to make noise that would be heard far beyond Keyworth.

"We just attacked unapologetically on every level, to bolster our team however we could, to try and get some bite out of other people. We just went full bore," Ken said in a 2015 interview.

At Detroit's first game, when the first goal went in, they passed around smuggled flares like sparklers at a Bonfire party.

"Everyone learned that day how bad sulphur is for your lungs, and how hot they are in your hands," Ken reflected.

"We marched out and didn't think we would ever be allowed back again."

But they were. In the meantime their full-blooded, volcanic support attracted heat online and more and more members on the ground.

Dion Degennaro was one. Football was a family flame passed on by his grandfather, an Italian immigrant to Buenos Aires who grew up in the shadow of La Bombonera - Boca Juniors' home - before moving to Detroit.

Dion, like Gene and Ken, was at Detroit's first game. Unlike them, he was unsure whether the atmosphere was going to be superclasico or damp squib.

"I went to that first game not knowing what to expect," he tells BBC Sport. "But I was like 'oh man, this is really cool'.

"In fact, I was a little intimidated. I didn't know what to make of it. It wasn't until the first game of the 2013 season that I went over and got involved in that supporter section.

"It was just making that first step to not be too intimidated by 2,000 people chanting, letting off smoke bombs and wearing skeleton masks."

The skeleton emblem is part of a Goth-tinge that is a hallmark of Detroit City's hardcore. Its aim is representation as much as intimidation.

"We use a lot of skulls and skeletons and black and smoke," explains Degennaro.

"Everyone would call Detroit a dead city. And part of what we do as a group is embrace criticisms people have of us and turn that into something that can't hurt us.

"If Detroit is a dead city, we are going to be the walking dead. We are going to show there are still things happening here."

Despite their fearsome look, changing things for the better is a driving force among the Northern Guard - the main Detroit ultra group that the Butchers and Degennaro are part of.

Their mission statement lists two things they hate.

The first is Ohio. Quite why is unclear to an outsider. Degennaro says it is a running national joke and has the sales figures to back himself up.

In their early days, the Northern Guard produced a special scarf that featured Ohio directly after another four-letter word. At the MLS All-Star Game in 2014, a travelling Detroit City fan waved one as a cameraman framed him up in a crowd cut-away shot on national television. It has remained the Northern Guard's most popular piece of merchandise ever since, selling all around the country.

The second thing they hate is hate itself.

Last year, the club and its supporters raised more than $26,000 (£20,800) for the Ruth Ellis Center which cares for at-risk LGBTQ youth in Detroit as part of their annual Pride Raiser month.

Back in 2014, they were the first sports team in America to dedicate their shirts to LGBTQ inclusion in a competitive match.

Previous causes have included Freedom House, which protects asylum-seekers fleeing persecution, support for those affected by the lack of clean water in nearby Flint, and a campaign to end to gun violence.

What matters to the fans, matters to the club. Without a multi-million dollar television deal, without a billionaire benefactor, the club relies on the turnstiles ticking over and creating a connection that draws fans back time after time.

A shared morality rather than a business triangulation motivates Mann, though. The big-league teams might prefer apolitical opacity. He is clear.

"The causes we embrace as an ownership, and where our supporters are at, are typically more social justice orientated, left-leaning causes," he adds.

"Sport has a disproportionate, almost unjustifiable, role in our communities. We employ as many people as an oversized, fast casual restaurant, but we're in the newspaper, we're on TV regularly.

"So, with everything going on in the world and in our country now, if we didn't use that to highlight the positive things going on in our community it would be a wasted opportunity."

The club turns its gaze inwards as well. Put bluntly, Detroit City FC is a very white club in a very black city.

"I think in the early years, you had a lot of white soccer supporters coming in from the suburbs to support the team because it was this hipster, cool, fun thing to do in the city," explains Degennaro.

"Where we play in Hamtramck is one of the most diverse communities in the country. And I think over the last year or two we're starting to see a bit more diversity in the stands, but there is always, always, always room for improvement. We want to be involved in the community and we want them to be involved in what we are doing as well."

The Northern Guard has launched its own initiatives, donating equipment to local public schools, organising clean-ups, supporting foodbanks, and working with the club to distribute tickets to local people who might not otherwise come to matches.

The combination of inclusivity on one hand and riotous, raucous rejection of anything that is not Detroit City, at least for a few hours on matchday, has reversed the traditional flow of people away from the city.

"Coming to Detroit and coming to Keyworth is kind of a pilgrimage to lower division soccer fans in United States," says Degennaro.

"It is something to experience and something to see. It's an away day that if people can come to, they try to make it."

Some of the attention has been unwanted, however. With Detroit City having proved the viability of a Detroit football team, Major League Soccer prospectors circled.

A consortium that included Dan Gilbert and Tom Gores, who between them own the Cleveland Cavaliers and the Detroit Pistons basketball teams, with combined assets worth over $10bn (£8bn), came up with a plan to launch an all-new Detroit MLS team in 2016.

"Everyone assumed that would be the end of us," admits Mann.

But the momentum behind the bid petered out as wrangling over the location of a stadium convinced MLS to look elsewhere.

Investors have approached Mann in the past about pumping money into Detroit City itself, but those offers would have fundamentally changed what Detroit City is.

He wants the character of the club retained and says: "No-one's really come close to that threshold of being enticing to us."

Detroit has seen vanity project teams come and go in the past. The Detroit Cougars, part owned by motor scion William Clay Ford, lasted only two years in the North American Soccer League in the 1960s. Detroit Express signed British superstars Trevor Francis and Alan Brazil, but lasted only one year more in the 1970s. Detroit City's more organic development has produced deeper roots.

"We will always show up for the club no matter what, because that's what we're here to do but, personally, I would have a hard time seeing us sell out to billionaires," Degennaro says.

"And the type of support that I like, I would say it's not really welcome at that level. They don't want people like me and supporters groups like us."

For now, no-one is coming to Detroit.

The club's first fully professional season is stalled after just one game - a 2-0 win away to LA Force - because of the coronavirus outbreak.

Since play halted, Detroit has become a hot spot in the US outbreak, with only New York and neighbouring New Jersey suffering more cases or deaths than the state of Michigan. State Rep. Isaac Robinson - who represented Detroit City's home of Hamtramck - was one of those to die.

English manager Trevor James arrived in January 2019 and has been tasked with overseeing the transition to the fully paid ranks. For now, his plans for a maiden season in the third-tier National Independent Soccer Association are on ice.

More urgent than the scoresheet is the balance sheet. The same direct reliance on matchday revenue and fans in the stands that has given the club its independent spirit has left Detroit City especially vulnerable.

Although they have paid back the investors who helped renovate Keyworth two years ahead of schedule, around half of the club's sponsors for this season, perhaps understandably, have not delivered their dues.

While they wait for those and government relief funds to arrive, the ownership group, led by Mann, have taken out loans against their homes to bridge the gap.

For a club that has rejoiced in defying people's preconceptions of Detroit, it is another difficult time. But right now Mann is not concerned about those beyond the city limits.

"I think 10 years ago I was much more defensive about Detroit, selling the club as something that put the city in a positive light. That used to be a driving factor in my life, both professionally in politics and with the soccer team.

"But at the end of the day we are doing this for Detroiters. We have created a special experience for people here in the city. Our goal is always to be Detroit's team - to have a club that resonates here in the community.

"When we get through this and get back to Keyworth. It's going to be a hell of a party."

Like all good parties, it will be loud and it will be fun. And it will probably upset a few people along the way.

Comments

Join the conversation

This club is about real fans, real community. Its what football used to be about here too....

I enjoyed many great games coaching AFC Cleveland in Detroit. Good luck and keep it going guys!

as a supporter of a pimp club - Man City - this article and the story of Detroit City is brilliant imho. Money & the ready made PR available in top flight football means it's attracted some dubious people. Reading about Detroit City really brought back fond memories when my club & its fans were outsiders & we felt like we were taking on the footballing world. Success is a two edged sword

I've never been interested in 'corporate' entities owned by people who don't really care for anything but the bottom line.

I hope Detroit City and Detroit the City recover and continue to re-grow. It's what a local sports club should look like.