Lost for Words – what happens to language in the onset of dementia?

"For many people with dementia, the first sign that something’s wrong is a change in how they speak. They might struggle to find a word, repeat themselves, or stumble and hesitate. For those who know more than one language, like my dad did, the picture can be even more complicated."

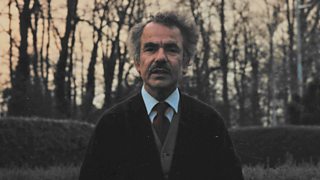

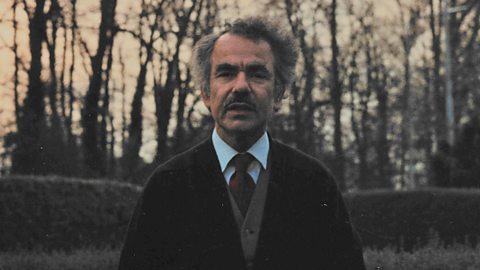

In Radio 4's Lost for Words, David Shariatmadari explores the science of language, dementia and ageing as he reflects on his own father’s experience.

Ebrahim was a doctor who moved to England from Iran in the 1960s. He started working for the NHS and in 1972 married an Englishwoman, my mum. He spoke fluent English at work and at home with us, and kept up his Farsi, also known as Persian, with regular phone calls and letters home. Fast forward 25 years and we began to notice that something wasn’t quite right.

My sister, Helen, takes up the story. “I always remember thinking it started when me and Mum went to Iran with him, six years before he died, because he kept talking to us in Persian and talking to the Persians in English.”

“He didn’t recognise for a few sentences that he was using the wrong language. That's when I thought, okay, he's not functioning normally.”

As time went on, his speech became more halting in general, and he often got confused. Eventually he was diagnosed with Alzheimers, and his mother tongue began to crop up more and more. It caused practical problems for our family because we didn’t really know Farsi – I’d just started studying it at university – but my mum, sister and brother hardly spoke any.

Because of dad’s bilingualism, I’ve always been fascinated by language. I’ve written a book about how it works, but one thing I’ve still not got to the bottom of is how dementia affects communication, and what was happening in my dad’s brain that meant his English deteriorated and his Farsi remerged.

I turned to neuroscientist Dr Thomas Bak for some answers, asking him whether my dad’s return to his first language was a typical pattern in dementia.

“There are studies suggesting that this going back to the first language is very very common, but it is not the only pattern,” he tells me. “So indeed, you have people returning to the first language, but you have also some people in which the first language seems to be more impaired. And one of the fascinating aspects of this work is to try to find out what are the factors – biological, psychological, and social, that can determine what happens with language.”

Temporal gradient

Dr Bak explained that one of the most important of these is the idea of “temporal gradient”, where older memories are preserved better than newer ones.

“Very often family members say ‘he cannot remember what he had yesterday for breakfast, but he can still tell me the names of his friends from school’ and so on. You remember things that are in your memory for a long time because they have been consolidated very well. Whereas things that have entered later on are less stable and more prone to loss.”

As for my dad, “his first language was very strong for the first decades of his life. And then English came, so there was a kind of switch from one to the other language. It seems that this early language network was stronger. And that's why it could withstand the changes of dementia to a certain degree.”

Lost for Words

David Shariatmadari explains how his father reverted to his native Farsi through dementia

The science behind it is fascinating, but I’m also curious about how we can help people who find themselves in this kind of situation. At the last census there were 4.2 million people in the UK whose main language wasn’t English – that’s an awful lot who could find themselves, later in life, unable to communicate easily with family and caregivers.

At the last census there were 4.2 million people in the UK whose main language wasn’t English.

Luckily, help is at hand. Renate Winkler is the co-founder of Guardian Carers, which specialises in providing bilingual help in a range of languages, from Arabic to Mandarin.

“If you're not able to communicate, clients get very frustrated. And by getting a carer that speaks the same language they are able to express themselves and they're able to tell them simple things like ‘I want to eat now, I want to go for a walk’. They're able to talk about their life. They’re able to talk about their childhood.”

One of their clients is Joe. His Italian mother Rosa, who has dementia, seemed to lose the ability to speak English quite suddenly, after a spell in respite care. “They would ring us up and say, look, she's not conversing in English. She's just chatting away in Italian. They would put mum on the phone to us to express what she wanted.”

So when she came out, they knew they needed to find an Italian-speaking carer. “We found this wonderful carer, Lenuta; she's very caring, very kind. And they've got a wonderful bond. There are no language barriers. So that's great.”

Multilingualism

It would be a mistake to think from all this that speaking more than one language just creates problems if you develop dementia. There’s also evidence that my dad’s fluency in two languages might have actually helped him. As Thomas Bak explains, multilingualism seems to stave off the symptoms of dementia, at least for a few years.

“We did a study in Hyderabad, in central India, and we found the bilinguals developed dementia over four years later than monolinguals.”

Bak even suggests that it’s normal for our brains to speak more than one language. “If you look through most of human history, most people have been multilingual. Monolingualism is a relatively late phenomenon. So from this point of view, it's less that multilingualism brings advantages, and more that monolingualism is a risk factor.”

Dementia is always a cruel illness: it felt particularly unfair that my poetry-loving dad, who enjoyed using language so much, was robbed of it towards the end. But it’s comforting to know that the fact he was bilingual may have given us more lucid years with him – and fascinating to learn that speaking more than one language could help all our brains stay healthier for longer.

-

![]()

Lost for Words

Struggling to find words might be one of the first things we notice when someone develops dementia, while more advanced speech loss can make it really challenging to communicate with loved ones. And understanding what’s behind these changes may help us when caring for someone with the condition.

Related Link

Psychology and lexicography on Radio 4

-

![]()

All in the Mind

Clauda Hammond presents Radio 4's magazine radio programme about psychology and psychiatry,

-

![]()

Word of Mouth

Michael Rosen presents Radio 4's series exploring the world of words and the ways in which we use them.

-

![]()

File on 4: Dementia – The Facts

What is "dementia", and what does the latest research reveal?

-

![]()

Word of Mouth: Communication and Dementia

Michael Rosen explores how to communicate with people with dementia.